After spending a term with my head buried in grammar specifications and debugging tokens, I wanted to write down a few thoughts before they fade away. The Foundations of Programming Languages course I took wasn’t just about compilers. It taught me how to think about programs from the ground up.

What follows are the parts that stuck with me the most.

Why build a compiler at all?

The course opened with three deceptively simple questions: Is this program valid? What does it mean? How do we run it efficiently? The first question leads to syntax and type checking, the second to precise semantics, and the third to the nuts and bolts of interpreters and code generation. Answering them turned into a semester-long journey through formal languages, grammars and static analysis. I discovered that understanding the tools we use every day requires diving into theory, but thankfully in small, digestible steps.

Lexing, parsing and all that jazz

Our project started with a tiny language and a working parser framework using JFlex and Java Cup. While the basic scanner and grammar were provided, extending them taught me how lexical analysis breaks source code into tokens and how parsing reveals program structure. Even with a foundation to build on, modifying grammars felt like teaching a computer it’s ABCs where just about every addition risked the dreaded “unexpected symbol at line 1 column 5”.

Once the parser worked, we built an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) to represent programs in a structured way. Each node corresponds to a language construct (like +, if, or while) and contains children for its subexpressions. Walking the tree lets you interpret or analyze the program without worrying about parentheses or operator precedence. Our early interpreter evaluated the tree directly, assigning values to variables in a simple state map. It was slow and ugly, but I found it incredibly satisfying to see how a language comes to life.

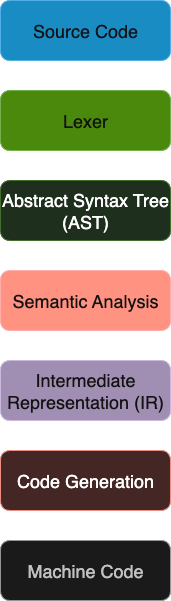

Here’s a simple diagram of the pipeline we ended up implementing, from raw source to executable output:

Along the way we learned about attribute grammars, which provide a way of annotating grammar rules with extra information such as types or symbol table entries. These attributes can flow up and down the parse tree, letting you implement tasks like type checking by extending the parser specification. It was the first time I’d seen code and theory blend so neatly, and it really drove home how formal methods can guide practical implementation.

Abstract interpretation in plain language

One of the most mind-bending (or rather head banging) topics we covered was abstract interpretation. The goal is to reason about all possible runs of a program without actually running it. We did this by classifying variable values into abstract categories: negative, zero, positive, or “any integer”. Instead of tracking exact numbers we tracked which category a variable belonged to, and we defined abstract versions of +, -, * and / that work on these categories.

For example, if x is positive and y is positive, then x + y is definitely positive. But x - y could be negative, zero or positive depending on the actual values, so the result becomes “any integer.” With this machinery you can prove facts like “this division will never divide by zero” by checking that the divisor’s abstract value is never zero. I initially thought this felt like fuzzy arithmetic, but I came to appreciate its incredible power. Here’s a small sketch of the sign abstraction we used:

What blew my mind was that this abstract evaluation is completely formal. You write inference rules just like operational semantics, but the values are drawn from a tiny lattice of possibilities. The “any integer” value sits at the top of this lattice, representing our complete uncertainty about a value’s sign. Suddenly static analysis wasn’t just compiler magic anymore; it became a logical system I could understand and extend.

Control-flow graphs and seeing your code as a graph

After we had an interpreter and a type checker, we moved on to generating an intermediate representation called three-address code. The idea is to break complex expressions into tiny instructions like t1 = y + z and x = t1 + w. From there you can build a control-flow graph (CFG) where each node is a basic block (a straight-line sequence of instructions) and edges represent possible jumps.

Working with CFGs was surprisingly visual. We learned how to compute dominators (blocks that must be executed before others), post-dominators (blocks that always execute after), and how to find loops by looking for back-edges. I found it fascinating that these concepts form the backbone of many optimizations like register allocation and common subexpression elimination. Even if you never write a compiler again, understanding CFGs changes how you think about if statements and while loops. Your code suddenly looks like a network of possibilities rather than a flat sequence of statements.

Operational semantics and type systems

We also circled around to operational semantics. Instead of asking “how do I implement this?” the question becomes “what does this program mean?” You can prove that your compiler preserves semantics by showing that translating a program to assembly and running it yields the same result as evaluating it directly. The formalism felt a tad unecessary at first, but it later gave me confidence that optimizations weren’t changing the program’s meaning.

We also compared static and dynamic typing. In statically typed languages like Java, every expression has a type known at compile time, and the compiler can reject code that tries to add a string to an integer. In dynamically typed languages like Python, types are attached to run-time values, and errors are detected at run time. Both approaches have trade-offs: static typing catches bugs early and can enable better optimizations, while dynamic typing offers more flexibility but might surprise you later.

Final thoughts

Building a compiler (albeit a HIGHLY simplified one) from scratch is the programming equivalent of building a bridge. You need a solid understanding of the ground (the syntax and semantics), a blueprint (the grammar and analysis), and the right materials (data structures, algorithms, and a lot of coffee). What made the course special for me was seeing how theory and practice feed into each other. Grammar rules are backed by formal language theory, static analyses are backed by lattices and fixed-points, and yet you write actual code to make it all work.

Special thanks to Professor Rountev for making this course so memorable.