After years of reading about crypto and messing around with blockchains (and sometimes losing my head over gas fees), I finally sat down with the original document that started it all. What follows are my notes from the early sections of Satoshi’s whitepaper mixed with a few personal thoughts.

Many thanks to Professor Venkatakrishnan for taking the time to discuss this topic with me.

Why we need a digital cash

The paper starts with a problem that’s so common we barely notice it anymore: online payments rely on banks and payment processors. This works most of the time but it means transactions can be rolled back, merchants have to trust your card company to pay up, and you have to hand over extra personal info every time you buy something. With cash, you just hand it over and walk away.

Satoshi’s solution combines a peer-to-peer network with cryptographic proof so two people can pay each other directly. No trusted third party and no one who can reverse the payment afterwards. Every transaction gets timestamped and chained together so the same coin can’t be spent twice. Sounds simple on paper but it took decades of work for someone to piece it all together.

Small digression: It reminded me of how barter gave way to commodity money and later paper currency. People will always come up with something new when the old system doesn’t quite fit the problem, even if it’s a messy workaround at first.

A chain of signatures (and why double spending is a pain)

An electronic coin is a chain of digital signatures. Each owner signs a hash of the previous transaction and the next owner’s public key. Problem is, nothing stops someone from signing that coin twice and giving it to two different people.

In normal payments the bank prevents that. Without a bank, everyone needs the same view of the transaction history. Satoshi proposes broadcasting all transactions to the network so nodes can agree on a single shared history. That way if Jonas gets a coin from Bob, he can check the ledger to see if it’s already been spent.

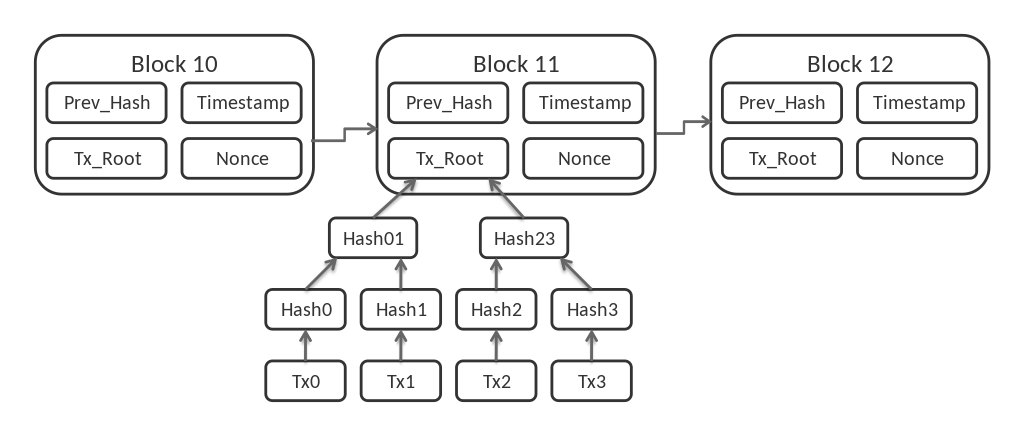

Here’s a basic diagram of a Bitcoin block. Each block points to the previous one through its hash and has a Merkle root summarizing all transactions. There’s also a timestamp and a nonce that miners adjust until the block’s hash is under a target value:

It’s not just a spreadsheet, the trick is that no one can alter an old block without redoing the proof-of-work for all blocks after it.

Incentives and the 21 million question

Why run the network at all? At first, miners get new coins for creating each block. Later, as the reward drops, they earn from transaction fees. It’s a bit like digging for gold and getting paid in the gold you find.

The 21 million coin limit isn’t because of some technical number cap. Satoshi just picked it, kinda. This raises the question: if supply is fixed and demand grows, do people just hold instead of spending? That could slow the economy, maybe that’s why other projects experiment with burning coins or changing supply rules. Bitcoin keeps it conservative, whether that’s good or bad probably depends who you ask.

Shrinking the blockchain

If every transaction is kept forever, won’t it get too big? The paper uses Merkle trees to compress old data. Only the root hash stays in the block header and old transaction details can be pruned once enough blocks are added above them. Block headers are tiny (around 80 bytes) and grow at a rate of ~4 MB a year, which is miniscule by present day standards.

Note to self: This means older receipts can be shredded as long as the cryptographic “fingerprint” stays.

Proof of work and one CPU = one vote

The network needs a way to agree on one history. Proof-of-work makes voting power proportional to computing power. The longest chain, meaning the one with the most work, is the winner. Difficulty adjusts so blocks come every ~10 minutes.

It sounds fair on paper but mining quickly became dominated by big operations. I also wonder if some group got a massive jump in computing power, could they rewrite history? In theory yes, but in practice it might just lead to forks and competing versions of the truth.

To picture the network, think of this diagram: each node connects to a few others, no central hub, and transactions ripple through until everyone sees them.

To close

The first sections of the whitepaper outline a way to make payments without relying on banks using cryptography and a gossip network. The idea is simple, the implementation is where the magic is. Merkle proofs, consensus rules, incentives all work in symphony to hide layers upon layers of complexity.

Reading it fresh reminded me that crypto isn’t just about prices or funny looking animals. It’s about finding ways for strangers to agree without trusting a referee.